The Bokashi Paradox: 5 Surprising Truths About the Soil Booster That’s Disrupting Waste, Outperforming Compost, and Even Taming Weeds

Bodemdag 2024

The Hidden Value in Our “Green Waste”

From roadside clippings and hedge cuttings to park grass and autumn leaves, UK councils and land managers generate mountains of green material every year. Most of it is hauled to composting facilities or energy-from-waste plants, racking up significant costs in haulage and gate fees.

But new evidence from large-scale trials in the Netherlands shows that this material doesn’t have to be a liability. With Bokashi fermentation, it can become a powerful soil improver that keeps nutrients local, cuts costs, and supports healthier soils.

1. It’s effective, but still sits in a grey legal zone

Dutch pilots backed by municipalities and water boards (like those in Leeuwarden and Dantumadiel) show that Bokashi can be produced safely and at scale (Blauwdruk Bokashi, 2024). Councils are already using leaf-Bokashi to improve survival rates of newly planted trees and reduce irrigation in parks.

Yet, as in the UK, regulation hasn’t caught up. Fermentation of green residues isn’t yet formally recognised in waste or fertiliser law, leaving it in a grey area. Here in Britain, that means Bokashi often sits outside permitted waste treatment frameworks, even though the environmental risks are no greater than with composting.

2. It preserves more carbon than compost

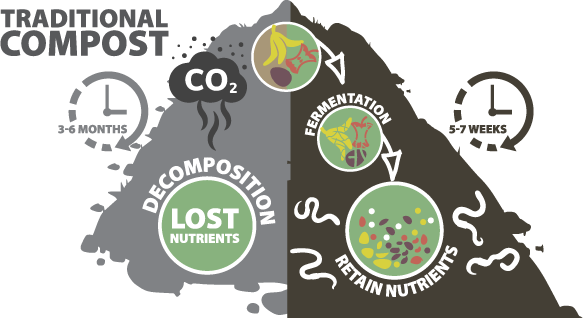

Research consistently shows Bokashi retains 94–97% of original biomass, compared with 50–60% losses during composting (Blauwdruk Bokashi study, 2024 PDF).

That means more organic matter and nutrients make it back into soils. The trade-off is that Bokashi tends to deliver a fast “pulse” of food for microbes, while compost provides more stable long-term humus. But in a climate where councils are pressed to cut emissions and farmers are looking at carbon markets, this efficiency matters.

3. The economics are game-changing

The Blauwdruk Bokashi study modelled a 5 km “green station” in Friesland, where roadside clippings are processed locally. The numbers are eye-opening:

Councils saved 43–64% compared with sending clippings to conventional composting.

Farmers saved 87% compared to buying equivalent compost.

Transport emissions were cut dramatically—86 lorry trips shrank to local tractor runs.

These savings mirror UK conditions, where waste disposal budgets are tight and haulage distances are growing. A similar localised model here could free up millions for frontline services.

4. It tackles weeds—including knotweed

Concerns about spreading weed seeds have been addressed in Dutch pilots: final Bokashi typically contains fewer viable seeds than certified compost.

Even more surprising, fermentation can neutralise invasives. Trials have successfully produced Bokashi made entirely from Japanese Knotweed, turning one of the UK’s most feared plants into a safe soil improver (Cvejić et al., 2021, cited in Blauwdruk Bokashi).

For councils spending millions on eradication, this is potentially transformative.

5. It feeds soil microbes more than it boosts yields

Long-term trials across arable and grassland systems show Bokashi consistently increases soil microbial biomass more strongly than compost or fertiliser.

But crop yield responses are mixed. Grasslands often benefit, but maize and cereals don’t always respond immediately. The reason is Bokashi’s relatively high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, which temporarily locks up nitrogen during decomposition.

So, while it may not be a quick fertiliser replacement, Bokashi is a powerful investment in soil structure, resilience, and long-term fertility.

From “Waste” to “Resource”

Both the Blauwdruk Bokashi study (PDF) and the Noardlike Fryske Wâlden initiative stress a cultural shift: clippings, leaves, and weeds must be seen not as waste, but as raw material.

For the UK, this could mean:

Councils slashing disposal budgets.

Farmers accessing cheaper soil amendments.

Landscapes becoming more resilient to drought and stress.

Even invasive plants becoming part of the solution.

The paradox remains: Bokashi is proven, popular, and practical—but policy hasn’t yet caught up. If the UK reframes green residues as a resource, Bokashi could play a central role in a more circular, cost-effective, and climate-smart land management system.