World Soil Day: Healthy Soils for Healthy Cities (and Why Your Compost Bin Matters)

Every 5th December, World Soil Day quietly comes and goes while most people are thinking about Christmas shopping, not subsoils. But this year’s theme – “Healthy Soils for Healthy Cities” – lands right in the middle of the places we often forget soil even exists: under pavements, car parks, housing estates and industrial estates.

For those of us working with compost, Bokashi, and living soils, this isn’t just a nice slogan. It’s a very practical question:

What would it look like if our towns and cities started treating soil as infrastructure – as essential to health and resilience as pipes, wires and roads?

The Invisible Soil Beneath the Tarmac

More than half of the world’s population now lives in cities, heading towards 68% by 2050. Most people picture cities as concrete and glass – but there is still soil everywhere:

Beneath street trees and verges

In parks, playing fields and school grounds

On allotments, community gardens and smallholdings at the edge of town

Under every new housing development, compressed by machinery and buried under turf

These urban soils quietly:

Filter and store water, reducing flooding and runoff

Store carbon, helping buffer climate change

Support biodiversity, from microbes and earthworms to pollinators and birds

Grow food, whether that’s a shared bed of kale or a full-blown market

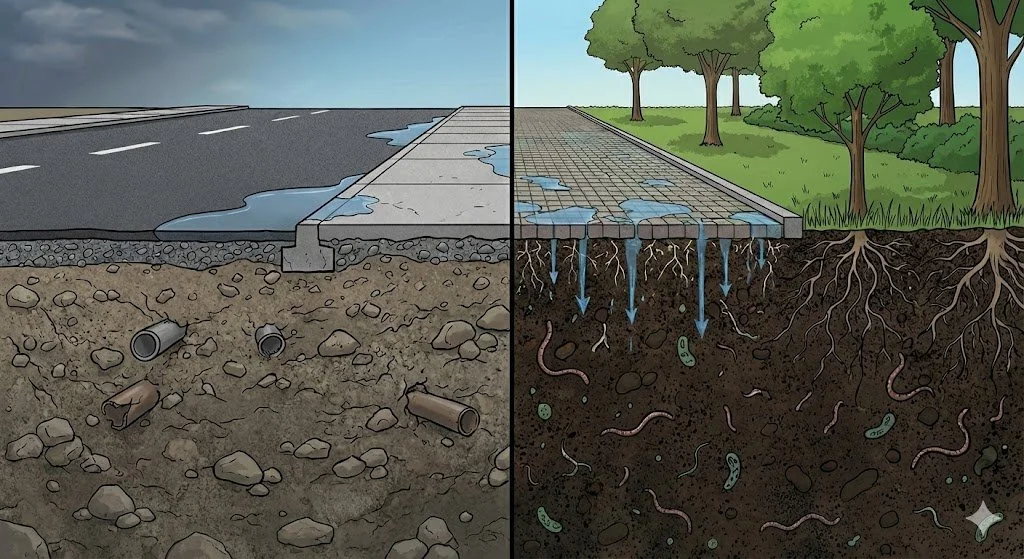

Yet the bulk of city planning still treats soil as something to move, flatten, compact or cover. Once it’s sealed under tarmac or slabs, its ability to infiltrate water, host life and cycle nutrients is dramatically reduced.

If we’re serious about “healthy cities”, we have to get serious about urban soils.

From Waste Streams to Soil Streams

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most cities are exporting fertility and importing problems.

Leaves, grass clippings and prunings are swept up as waste, not seen as raw material for humus.

Food waste is collected and hauled away, often at high cost, instead of being transformed into living soil amendments close to where it’s produced.

Construction compacts subsoil, strips topsoil, then brings in sterile turf on top – a “green carpet” with very little life underneath.

World Soil Day is a good moment to flip that thinking:

What if every estate, school, and neighbourhood treated organic “waste” as feedstock for urban soil regeneration?

That’s where systems like Bokashi, composting, vermicompost and well-managed slurries/digestates come in. Not as magic bullets, but as practical tools to:

Keep nutrients cycling locally

Build soil organic matter (SOM) and structure

Support the biology that makes urban soils function again

Soil Is Not Just “Dirt + Fertiliser”

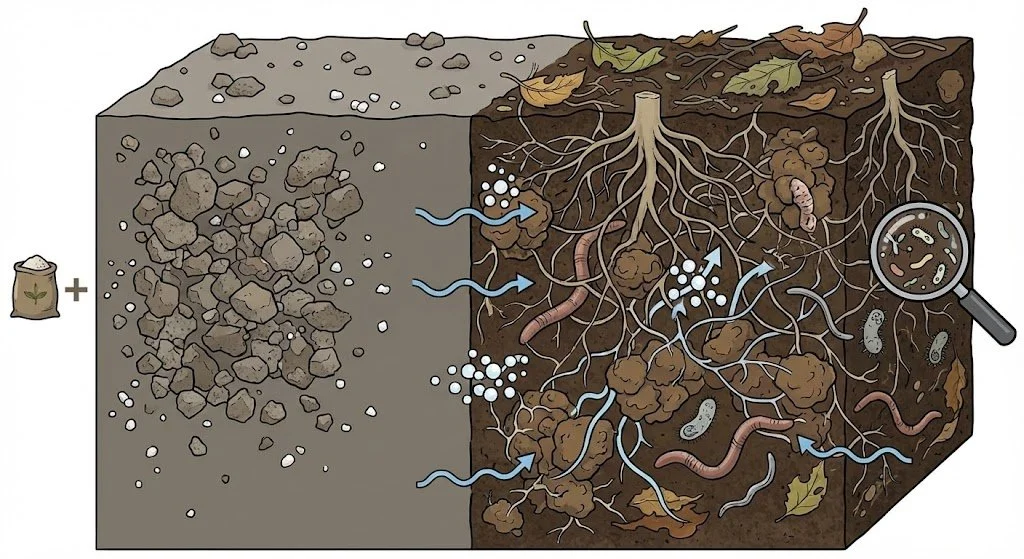

There’s a growing consensus in soil science that the old idea of soil as an inert mineral container is simply too crude. Yes – plants need mineral nutrients. But:

The soil food web (bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, earthworms and more) is what stabilises those nutrients, builds aggregates, and keeps water and air moving.

Soil organic matter – the modern, more nuanced successor to the old “humus” concept – is a dynamic continuum, not a single magic substance. It’s constantly being built and broken down by microbes and roots.

In cities, that living engine is often damaged by:

Repeated compaction (cars on verges, heavy kit, construction)

Total sealing (tarmac and impermeable surfaces)

Periodic stripping of “messy” organic matter – leaves, woody debris, cuttings – that biology actually needs.

So a “healthy soils for healthy cities” agenda has to include biology, not just “NPK + testing”.

Three Practical Shifts Cities Can Make

World Soil Day campaigns can sometimes feel abstract. Here are three very tangible changes any town, council or local network could start working towards.

1. Turn Green Waste into High-Quality Compost, Not a Cost Centre

Instead of paying to haul leaves, branches and park cuttings away, cities can:

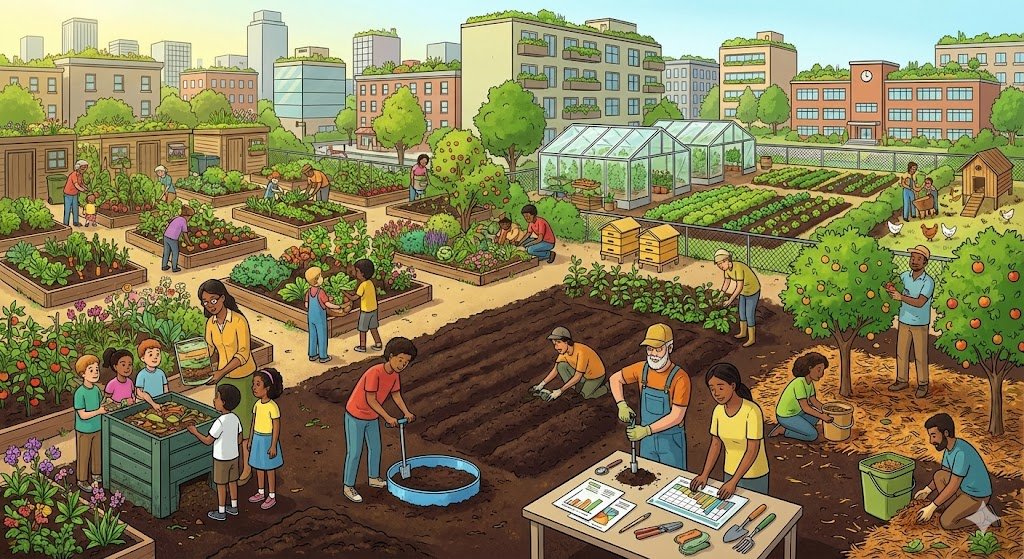

Set up local composting and Bokashi hubs at parks, depots, allotments and schools

Blend leaf mould, shredded woody material and food waste (where permitted) into biologically rich compost and mulches

Feed that material straight back into:

Done well, this not only builds SOM and structure but also helps buffer stormwater and reduce flood risk – an increasingly critical function in urban

2. Protect and De-compact the Soil We Still Have

Compaction turns living soil into something closer to brick:

Water runs off instead of soaking in

Roots struggle to penetrate

Oxygen-starved zones favour the wrong kind of biology

Simple but powerful actions:

Designated no-parking areas on verges and greens

Mulching and light surface cultivation around street trees rather than bare, trampled circles

Using tools like subsoilers/air spades once, followed by organic amendments and permanent ground covers, to repair damaged soil instead of re-compacting it every year.

New work with “soilsmology” – using seismic waves to measure compaction and structure – is even starting to give us non-destructive ways to map urban soil health under our feet.

3. Bring Food Growing Back into the City Fabric

You don’t need thousands of acres to make soil meaningful:

Pocket allotments and community gardens

Edible planting in parks, estates and school grounds

Small commercial urban farms on underused land

Wherever people grow food in cities, they also tend to care about soil. Those are natural hubs for:

Demonstrating Bokashi, composting and mulching

Monitoring soil health (organic matter, bulk density, infiltration) in a very practical way

Teaching the next generation that “waste” is feedstock for the soil, not something to hide in a black bag

What World Soil Day Means for Households

All of this can sound big and structural. But at home, the message is beautifully simple:

If you eat food, you manage soil – whether you realise it or not.

Every banana skin, coffee ground and carrot peeling has two possible futures:

Exported – bagged up, hauled away, often at public expense, and someone else has to manage the carbon, nitrogen and odours.

Circulated locally – through Bokashi, composting or worm bins – and returned to pots, beds, borders or a shared garden.

For urban households, that means:

Using kitchen-scale systems (Bokashi, wormeries, hot bins) so that even flats and small spaces can keep nutrients in circulation

Swapping “neat, bare soil” for living mulches, clover under fruit trees, and a bit of wildness for insects and soil life

Seeing every handful of compost not as “recycling”, but as regenerating urban soil infrastructure.

A Different Kind of City Planning Question

Most city masterplans still ask:

How many homes?

How many parking spaces?

How many square metres of “green space”?

World Soil Day gives us a chance to add some new questions:

How much water can our urban soils infiltrate and store in a heavy rainstorm?

How much organic matter can we build into our parks, verges and community spaces over the next decade?

How can we design neighbourhoods so organic “waste” never leaves the system, but feeds living soils locally?

Those questions sit right at the heart of this year’s theme: Healthy Soils for Healthy Cities.

A Simple World Soil Day Invitation

So, for this World Soil Day, here’s a very practical invitation:

If you’re a household: Start one new habit that keeps organic matter cycling locally – a Bokashi bin, a shared compost bay, or mulching your beds instead of sending leaves away.

If you’re a grower or community group: Treat your site as a local soil hub – demonstrate good composting, measure and improve your soils, and share the story with your neighbours.

If you’re in a council, school or estate team: Pick one site – a park, verge or school ground – and commit to managing it as soil, not just surface: less compaction, more organic matter, more life.

Because in the end, cities don’t float. They stand on soil – and the way we treat that thin, living layer will decide how resilient, healthy and liveable our urban life really is.