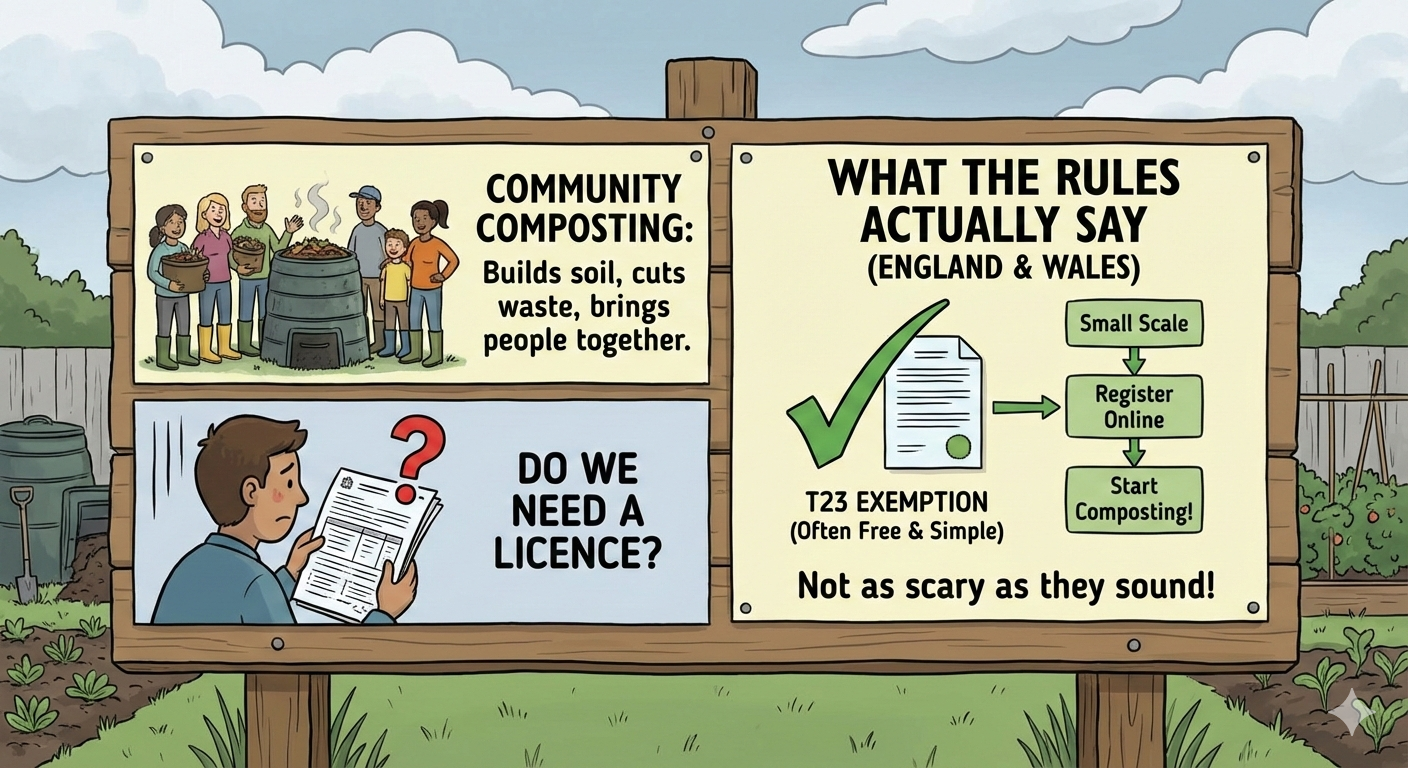

Community Composting in England & Wales: What the Rules Actually Say (and Why They’re Not as Scary as They Sound)

Community composting is one of those quietly powerful things.

It builds soil, cuts waste, brings people together, and turns “bin problems” into local solutions.

But if you’ve ever looked into starting (or formalising) a community composting scheme — at a school, allotment, community garden or shared site — you’ve probably hit the same wall:

“Wait… do we need a licence for this?”

The short answer: yes, but it’s simpler (and often free) than you might think.

This blog pulls together the latest clarifications from Environment Agency, insights from Garden Organic, and real-world community practice — so you can compost with confidence, not fear.

First things first:

shared composting a “waste operation”

This surprises a lot of people.

Under the Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2016, any composting in a shared space is legally classed as a waste operation.

That includes:

Schools composting food waste on site

Allotments with shared compost bays

Community gardens

Volunteer-run compost hubs

Projects collecting waste from nearby homes or cafés

This doesn’t mean you’re doing anything wrong — it just means the activity needs to sit within the Environment Agency’s framework.

The good news? Most community composting fits neatly into simple exemptions.

The two exemptions most community projects use

🌱 T23 exemption – aerobic composting

This covers traditional composting (bins, bays, windrows, in-vessel systems).

If you compost waste produced on site and use the compost there

→ up to 80 tonnes per yearIf waste comes from elsewhere or compost is used off-site

→ up to 60 tonnes per year

Materials can include garden waste, some food waste, cardboard, paper, manure and animal bedding.

🪱 T26 exemption – wormeries

This applies if you’re composting kitchen or canteen waste using worms.

Up to 6 tonnes per year

Covers food waste, paper and cardboard

“But we’re a community group — do we have to pay?”

This is where things recently got confusing.

Since July 2025, there are charges for registering T23 and T26 exemptions in general.

However — and this is crucial — groups working exclusively for a charitable purpose can still register for free.

That includes:

Schools

Community gardens

Volunteer-led composting groups

Informal community organisations (you do not have to be a registered charity)

At the moment, the free route is:

📞 Call the Environment Agency on 03708 506 506

The EA has confirmed they’re updating their website wording and systems so this becomes clearer (and online) soon.

Moving waste? You’ll also need a waste carrier licence

If your project transports compostable material — for example:

Collecting coffee grounds from a café

Moving food waste between sites

Then you need a Lower Tier Waste Carrier Licence.

Good news again:

It’s free for charities and voluntary groups

It doesn’t expire

You’ll also need to issue a waste transfer note when collecting from businesses (like cafés), but not from households.

Don’t forget: duty of care still applies

Everyone handling waste has a duty of care under the Environmental Protection Act 1990.

In practice, this means:

Manage waste safely

Prevent pollution, odour and pests

Keep basic records where required

Most well-run community composting schemes already do this instinctively.

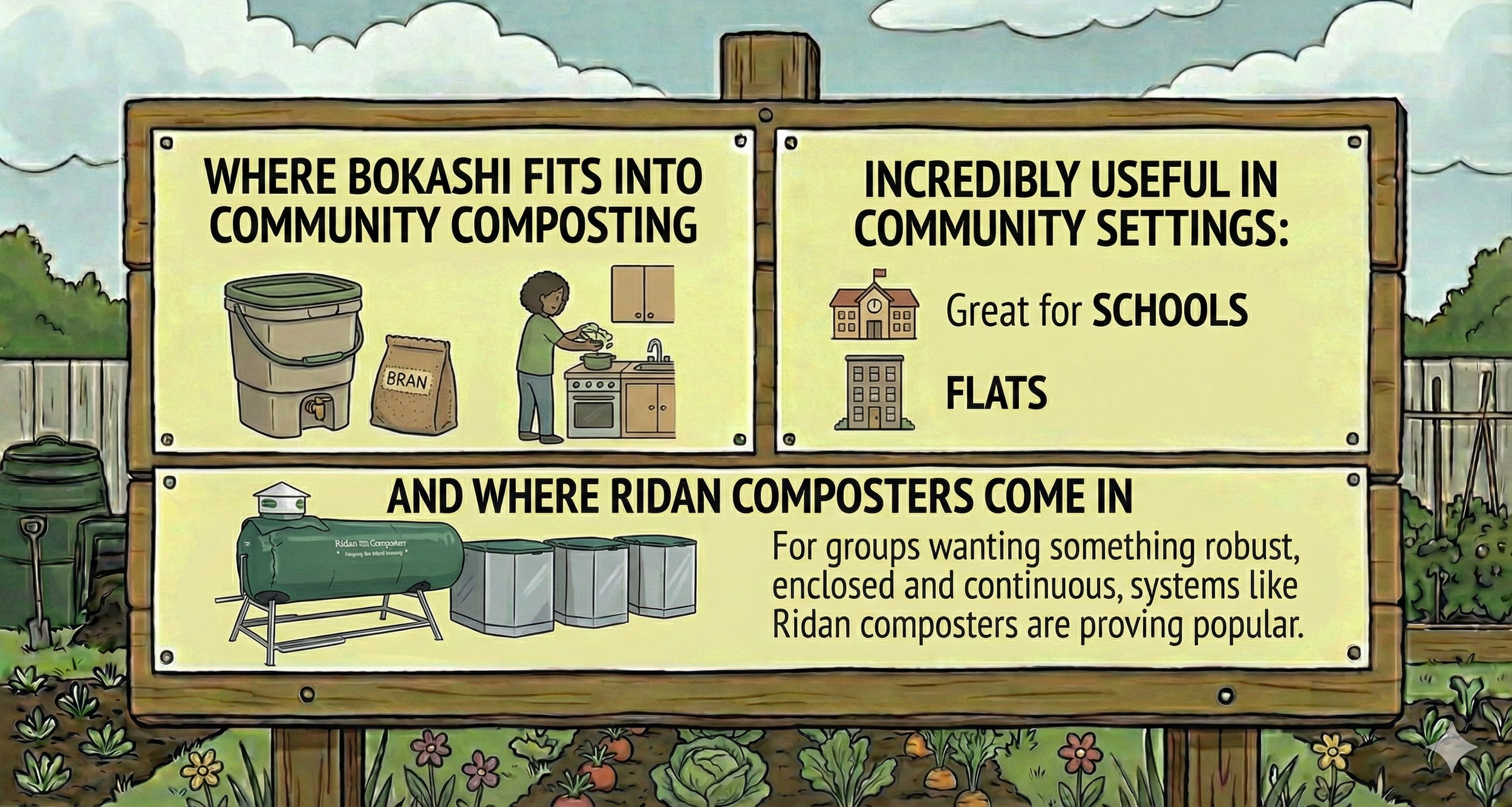

Where Bokashi fits into community composting

Bokashi often gets overlooked in regulatory conversations — but it’s incredibly useful in community settings.

Bokashi is a sealed, fermented pre-treatment for food waste:

Great for schools, flats and shared kitchens

No smells, no pests

Reduces pathogens and stabilises food waste before composting

In many community systems, Bokashi is used upstream, with the fermented material then added into a T23 aerobic composting system on site.

This:

Improves compost quality

Speeds breakdown

Reduces nuisance issues (especially food waste)

It’s a practical bridge between kitchen and compost bay — and increasingly common in schools and housing projects.

And where Ridan composters come in

For groups wanting something robust, enclosed and continuous, systems like Ridan composters are proving popular.

Ridan units:

Support aerobic composting on site

Are well suited to schools, estates and community hubs

Fit neatly within T23 exemption limits when correctly managed

Pair very well with Bokashi-treated food waste

They’re not “magic boxes” — they still need good practice — but they offer a practical, visible composting solution that ticks both operational and regulatory boxes.

Real-world reassurance: community composting works

There are fantastic examples across the UK — like the Bisley Community Composting Scheme in Gloucestershire — quietly processing tonnes of local waste, building soil, and strengthening communities.

As Garden Organic put it:

Don’t let the exemptions or licences put you off.

Most projects:

Start small

Register the right exemption

Learn as they go

And end up becoming local reference points for others

Useful links in one place

Garden Organic community composting support

👉 https://www.gardenorganic.org.ukWaste exemption guidance (overview)

👉 https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/waste-exemptionsT23 aerobic composting exemption

👉 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/waste-exemption-t23-aerobic-compostingT26 wormery exemption

👉 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/waste-exemption-t26-wormeriesWaste carrier licence

👉 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/register-as-a-waste-carrier-broker-or-dealer

Final thought

Community composting isn’t about jumping through hoops — it’s about doing the right thing, the right way.

Once the paperwork is understood (and honestly, it’s lighter than it looks), what’s left is the good stuff:

Healthier soils

Less waste

Stronger local networks

And that’s the bit worth composting for 🌱